Thoroughbred Logic: Keep A Door Open

“…perhaps one of the absolutely most important things to riding young, green, anxious or slightly nutty horses is that you cannot close all the doors at once — you must in fact leave at least one open and give them somewhere to go, lest they exit through a closed window or punch through the ceiling.”

Welcome to the next installment of Thoroughbred Logic. In this weekly series, Anthropologist and trainer Aubrey Graham, of Kivu Sport Horses, offers insight and training experience when it comes to working with Thoroughbreds (although much will apply to all breeds). This week, come along for the ride as Aubrey discusses her logic on always keeping a proverbial door open when working with a horse.

“When one door closes another one opens” is an all-too-commonly used adage apparently coined by Alexander Graham Bell. That said, while his upbeat saying regularly holds for jobs, relationships, and our life as riders and trainers (with our persistent need for optimism in the face of frustration and loss), I need to twist its meaning slightly to address an important training concept about — you guessed it — doors.

Perhaps, if we geared this adage more appropriately to the green, playful or anxious horses’ perspective, it would say something like, “When the last door closes, is time to break another one down.”

Needles Highway showing off his door-breaking potential during his first time in restricted turnout post stall-rest. Photo by author.

Riding horses is all about which doors you shut and which you leave open. I don’t remember when or where I learned this, so I unfortunately can’t give credit where credit is due. But perhaps one of the absolutely most important things to riding young, green, anxious or slightly nutty horses is that you cannot close all the doors at once — you must in fact leave at least one open and give them somewhere to go, lest they exit through a closed window or punch through the ceiling (yes, I’m stretching the metaphor…).

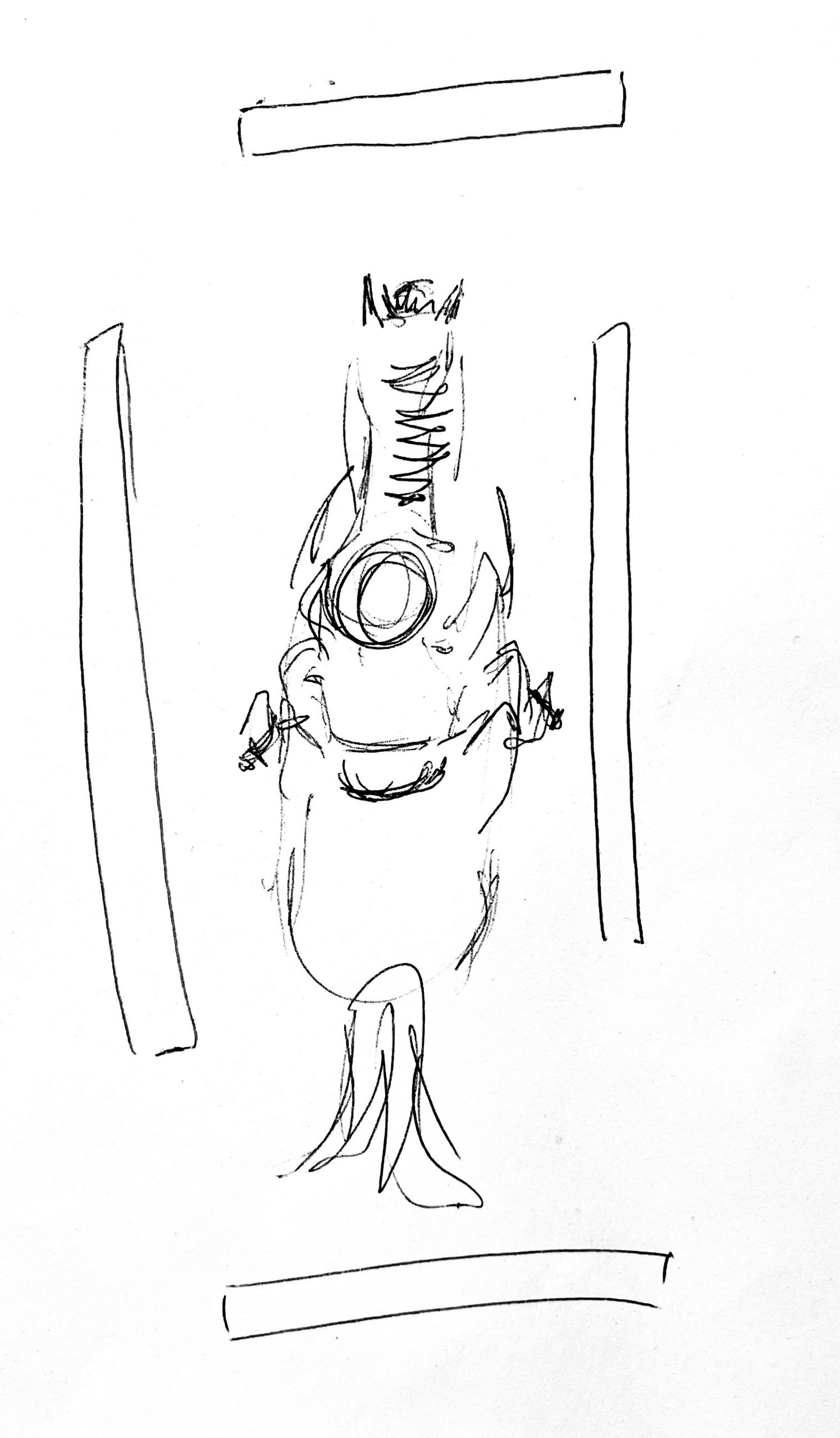

A diagram probably helps, so I’ll try to do my best sketch here… Think about it this way — there are four doors around the horse: one in the front, one in the back, and one on each side. There is also the door above the horse making it a bit of a box. If you “close” the right door (aka put your right leg and rein on), the horse will go left. Close the left door, they go right. Close both lateral doors and the horse either will go forward (more common) or backwards (hopefully only if asked to rein back). The rear door is closed by putting on “forward” leg etc. and the front door is controlled by your hands in relation to checking or containing movement.

The intentional closing of those doors (often in combination) is a way to think about how we use our aids to both direct and balance the horse. Such pressure can absolutely be a good thing, so long as their energy has somewhere productive to go. I find myself reminding students (and myself) regularly that one needs to soften the inside hand even on a spicy ride, as the horse needs to feel that there is a “space” (a cracked-open door) for them to move into and through.

If a rider locks down with both hands on a green horse (or any horse, really) it is likely to get frustrated. Often, the harder one holds, the more counterintuitively forward the horse goes. Lock down with ones’ hands and legs (AKA close all of those doors at once) and a horse will generally do one of many undesirable options: If they are moving, they may head toss, increase their speed, pull you forward onto their forehand, or simply break/bolt through a “door” and flip a rider off (figuratively, though maybe literally too). If at a halt, they may dance from foot to foot and *think* about the various ways they can get you to open a door so that they can go forward. If they get totally stuck and flummoxed, they might exit out back or the “overhead” door and stand up.

Madigan Cat is known for his bucking fits on the track, so at his first show I kept a front (go forward here) door open at all times. He was awesome. Photo by Amanda Woomer.

Sure, playful or anxious horses (or you know, your average green Thoroughbred) might do any of these things anyway. But they are much more likely to be the saintly rides we desire if we as riders are responsible about which doors we close and which we leave ajar. Moreover, knowing how to crack the right door open can help redirect energy and avert a tense or potentially dangerous situation.

Rhodie (Western Ridge) when he is feeling fancy and not looking to destroy a door. Photo by Cora Williamson.

Here are a few examples:

Let’s take Crafty (because he is mine and I can pick on him)… he’s my favorite complete nut job who regularly puts in lovely movements and then has days where he’s certain that jump pile at the end of the arena (that is always there) is going to eat him. So, when passing said muddle of hopefully repairable jumps, if I close the rear door (leg on, go forward) and then lock down the right and left leg and rein (lateral doors closed), he is going to potentially rear (the jump pile closed the front door for me), or try to scoot sideways through my hand and leg, likely running through whichever lateral aid is to the inside of the arena. If I don’t learn from experience, the whole ride will go like that — nice movement, then straight-up stupid when I get near the dicey side of the ring. Rinse. Repeat.

Not Crafty, but that’s the same “face” he makes at the jump pile before the tomfoolery begins. Photo by author.

Or, I can come to the ‘jump pile’ side with a plan and an already-propped open door. I’ll put him on a bend to the inside, leg yield him slightly towards the pile but keep the inside rein soft and open (like a foot away from his neck type of open). That is your propped door — that’s his emergency exit. If he wants to go somewhere, he knows he can hustle that direction, which, when on a bend and yielding towards the jump jumble does a reasonable job of carrying both of us in rhythm past the pile and on along the arena. Do that once or twice and generally the stupid disappears. (Do note, Crafty is far from actually stupid… BUT, he certainly is happy to act a fool whenever he sees fit).

With Rhodie (another easy-to-pick-on goober of mine), a different type of door-closing awareness is required. If I am asking for any form of collection and keeping light contact and leg, I cannot close both lateral doors or he will blast through one of them — usually to the left and run me sideways. His dragon dramatics are totally unnecessary but thankfully getting more manageable. So to prevent the high-speed crab walk, I need to make his tense moments productive — add a slight lateral movement, leave one leg (and the affiliated door) a touch softer than the other and encourage him to step into that softer, open space. Then, as soon as he is “good” — soft and compliant, I reward the effort with an open front door and we get to go more forward.

Rhodie (Western Ridge) making a decent attempt to break through the proverbial left door before giving into my inside hand and getting to go forward to the next fence. Photo by Cora Williamson.

Equally, a horse that bucks needs an open door and somewhere to go. A soft leading rein to a safe part of the arena or field will help keep the fits to a minimum. A horse can’t do nearly as much damage bucking while legitimately going forward (AKA porpoising is a lot easier to ride than bronc-ing). But if one locks all the doors and keeps them that way, the bucking fit can escalate dangerously.

Riding a friend’s super talented green bean the other day, I realized that I was giving him an opening right rein after each cross-country fence. This open door kept any potential hops on the backside to a minimum and directed him without having to think about it to the “safer” part of the field (away from a group of riders and the individual doing gallop sets).

Laura Edison’s talented jumping bean getting an opening right rein over an xc fence at Ashland Farm last Saturday. Photo by Laura Edison.

One can extend the importance of this training concept/awareness to the mounting block, to standing in groups, and to working with horses that rush or run backwards and rear, or have any common spook, scoot, bolt or buck. But more importantly, it extends to all of the not dramatic rides too — to when a horse is falling in on a turn, or tossing its head, dropping a shoulder, or getting behind a rider’s leg.

Knowing how to prop open or shut the *correct* doors to channel a horse’s energy in the desired direction takes time, effort and feel. That said, while all of this is terribly cliché, the first step is simply awareness. Being aware of what doors are closed, which are locked, and which you are leaving open, sets you up as a rider to better understand your horse and how you are encouraging or countering their efforts. At the end of the day, everyone — horses and humans — like to know that when indeed that one door closes, another opens.