Best of EN: Must Pass PPE

“The solution is not black and white, not an either/or. The pre-purchase exam is a good thing and we encourage them, but it does not remove the responsibility of horsemanship and management from the buyer and trainers surrounding the horse.”

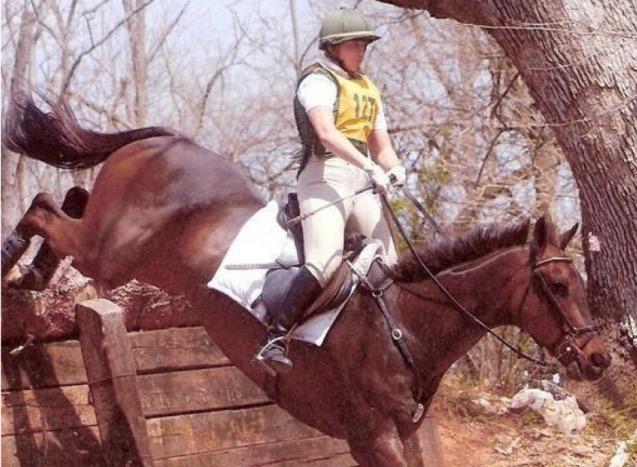

Sunday’s Thrill. Tie-back surgery, sounded like Darth Vader, chip in ankle, hock stuff, back stuff (but no radiographic changes — go figure), farrier’s nightmare, but ever held at any FEI jog. Photo courtesy of Clare Mansmann.

“Must Pass PPE.” Nothing makes me pause more than this phrase. You’ve seen it, maybe even have said it. It is frequently mentioned in ISO posts, messages, etc., and it is not meant to harm, but some people do not understand the depths of what they are saying. Let’s just at least start with this, with all due respect: there is no such thing as passing or failing a pre-purchase exam (PPE), and many who use the term would even admit that. It’s simply that it’s a quick, easy way to point out that you’re looking for a horse with the least amount of risk possible, aside from the fact that it’s, you know, a horse.

It may be speculated that the XYZ condition spotted in a radiograph won’t last at the upper levels, or that the horse will have problems later in life. Maybe. Shoot. There’s a long way between A and XYZ, and a whole lot of other troubles we’ll have to get through, mainly in our own riding, let alone worrying about the ifs, ands or buts in a crystal ball.

People will say they’ve had their heart broken by their last horse, by the last injury, the last colic, the last time they had to say goodbye, the last dream that didn’t come to fruition and they are desperate not to repeat the experience, hoping that a clean set of radiographs and perfect flexions will protect them. Or they are looking for that horse to take them or their child to the upper levels of competition, forgetting that the horse that takes you there is so much more than medical records, and rather often makes it in spite of those medical records.

And so the pressure on the sellers, the trainers, the owners, the vets, increases and, in turn, the pressure on the horse increases. That is a lot of pressure. A lot. Especially when we are talking about an animal who owes us nothing and whose only goal really is to stand and eat.

The process has evolved over time, and an argument stands as to whether that is good or bad or a little of both. The pre-purchases of yore were fact-finding missions. The physical exam ensured the horse was healthy and ready to work (i.g. no gaping hole in its heart). Findings were presented and it was up to the prospective buyer to make decisions. That’s a little simplistic, but is generally true, and most people from the days of yore, like myself, would agree. You tended to buy the horse you wanted, and you made it work or you didn’t. It either worked or it didn’t or some degree in between, but that probably had little to do with the PPE.

His heart, though? Bigger than his body. Photo courtesy of Clare Mansmann.

But humans love numbers and measurements and causation and reasons for why anything happens, and that’s not necessarily wrong, but it doesn’t always work. Technology has certainly advanced now. We can see things on a radiograph that we never would have seen before. But it seems that the relationship between advances in veterinary abilities and horsemanship is an inverse one. Horses are looked at as if that day predicts their entire future. Fitness, strength, shoeing and training are ignored. It’s the same as watching a free jump video and thinking that that is how the horse is going to jump with a rider, or watching a racehorse trot and thinking that’s how it moves. If we are to be stewards of these animals, horsemanship must be paramount, but it is not taught in school or online.

Excellent, talented, sweet, suitable, well-trained animals of all varieties are being marked as unsaleable without due process, despite being sound for work. What do we do with all of these horses who are in solid work, doing jobs, proving themselves, but won’t “pass a PPE?” Buyers are scared away from horses needing “maintenance,” despite that not being an actual medical term, envisioning needles, lameness and vet bills, when actual regular maintenance should come in the form of correct training and nutrition and, yes, horsemanship. When medical attention is necessary, then that care is a wonderful thing, but regular medical intervention should not be the norm and so often does not need to be the first line of defense.

Pre-purchase exams today seem designed for horses to “fail.” People have begun using the PPE as the deciding factor in whether or not to purchase a horse, rather than buying a suitable mount. They are relying on and putting pressure on veterinarians to choose their mount, rather than their trainer. And, that is not fair, as that is really not what that doctor went to school for. Many vets don’t even ride horses and certainly aren’t trainers or instructors, and it was never their intention to be.

There seems to be a disconnect between pre-purchase exams and veterinary care, and I offer this food for thought: If you’re in a PPE situation and an issue comes up (which it will), ask this to your veterinarian, “If I already owned this horse and we diagnosed this condition, or found this on a radiograph, what would you say and how could we best take care of this horse to continue our partnership?” The answer may bring a lot more comfort, education, and horsemanship than you think.

Sunday’s Thrill lived with us, happily and healthily, until we laid him to rest at 27 years old. Photo courtesy of Clare Mansmann.

The solution is not black and white, not an either/or. The pre-purchase exam is a good thing and we encourage them, but it does not remove the responsibility of horsemanship and management from the buyer and trainers surrounding the horse. We need to change our dialogue surrounding the process, be intentional with our words, be honest with ourselves and with others. The PPE does not remove the risk of horse ownership, and it won’t protect our hearts. It’s not even guaranteed to protect our wallets. But there are things that will help, that take time but cost little (I mean, as far as anything in horses goes). There is education, knowledge, hard work, the aforementioned time and a love and stewardship of the horse that supersedes the wants of the rider.

There could be thousands of rebuttals to my thoughts and, trust me, I’ve thought of every one of them, but if there is a niggling whisper of agreement, then there’s a place this conversation can go. For every story of heart-break, there are more heart-warming, more redemptive and, many times, more reasonable ones out there.