Painful vs. Non-Painful Lameness

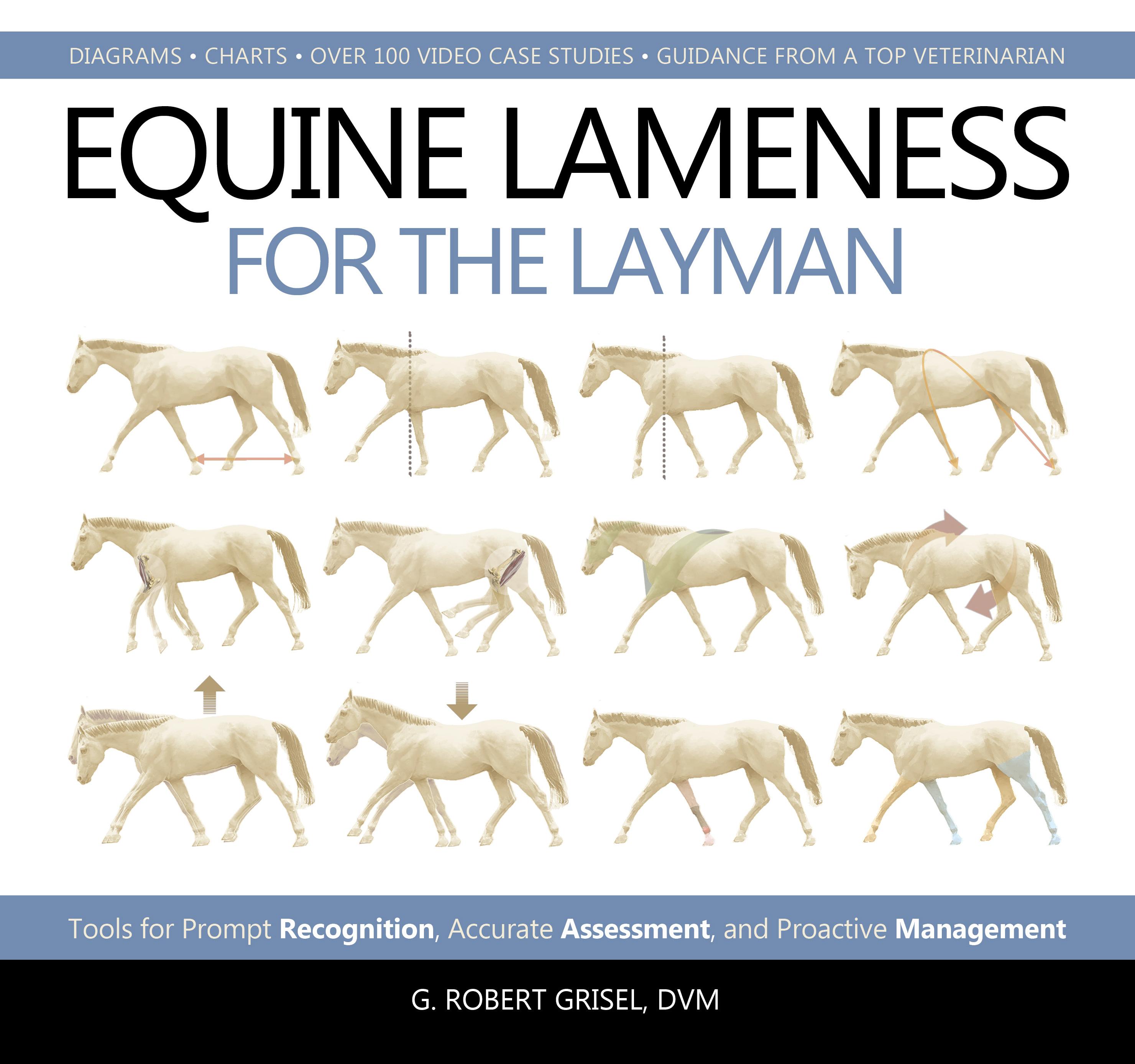

“To most of us, a lame horse is a horse in pain. While this is true in the majority of cases, gait abnormalities can also be generated by issues that don’t hurt.” Dr. Bob Grisel explains in this excerpt from Equine Lameness For the Layman.

To most of us, a lame horse is a horse in pain. While this is true in the majority of cases, gait abnormalities can also be generated by issues that don’t hurt. The adept observer has the ability to recognize both forms.

As you might imagine, pain-mediated lameness is easier to diagnose for the average veterinarian. Hands-on manipulation of the body and limbs (such as palpation and flexion testing) can be used to increase discomfort associated with specific anatomic regions, thereby helping the practitioners aim their diagnostic efforts. Local anesthesia (perineural and synovial blocks) can be used to confirm or deny suspicions with regard to potential sources of pain. The animal’s response to empirical treatment in the form of local anti-inflammatory or arthrotherapy can also help to implicate various structures as the point of origin.

Non pain-mediated issues, by contrast, cannot be accentuated through manipulation nor be “blocked out” during lameness examination. They are often invisible upon diagnostic imaging and refractory to medical therapy. Many non-painful issues, therefore, can only be diagnosed via their display of characteristic gait deficits. This is where meticulous visual analysis becomes a critical part of the workup.

Non-painful issues comprise those that are biomechanical (usually restrictive) and neurologic in origin. Biomechanical lameness usually results from abnormal interaction between soft tissue and bone. Since tendons, ligaments, and muscles attach to bone (directly and indirectly, respectively), they are most often implicated as sources for biomechanical lameness. Intermittent upward fixation of the patella (IUPF) and fibrotic myopathy of the hamstring musculature are two well-described biomechanical problems that occur in horses.

Horses can also exhibit non-painful lameness in response to neurologic disease. Neurologic lameness often arises as a consequence of compromised motor innervation (in which nerves are supplying inadequate input to the muscles that move the body and limbs) and/or decreased proprioception (in which reduced sensory output from the limbs affects spatial awareness). Neurologic lameness can be weight-bearing and/or non weight-bearing in nature, depending on the nerves and structures affected. Circumduction is a gait deficit most evident at the walk and often attributed to neurologic disease (visit www.getsound.com/tutorials/8a for a narrated example).

Non-painful issues usually produce non weight-bearing lameness. This is easily demonstrated via the application of a splinted brace to one of your knees. The splint, when properly positioned, should not be uncomfortable nor prevent you from bearing a normal amount of weight on the limb during full extension. Yet it will effectively prohibit flexion of your limb, thereby resulting in a visibly obvious gait deficit as you try to ambulate.

An excerpt from Equine Lameness for the Layman by Dr. Bob Grisel, reprinted with permission from Trafalgar Square Books (www.horseandriderbooks.com).

Leave a Comment